Scituate Lighthouse

Scituate, Massachusetts - 1811 (1811**)

History of the Scituate Lighthouse

Posted/Updated by Bryan Penberthy on 2014-03-04.

The area known as Scituate, derived from the Wampanoag term satiut meaning "cold brook," was settled by members of the Plymouth Colony and English immigrants as early as 1627. The town incorporated itself on October 5, 1636.

The town had a small, but protected harbor comprised of Cedar Point to the north and First Cliff to the south. Shallow water and mudflats sometimes made entry to the harbor challenging. Despite these hazards, the town developed a budding fishing fleet.

By the late 1700s, the fishing fleet had surged. A shipmaster named Jesse Dunbar along with other locals had requested a lighthouse in 1807 by petitioning the town's selectmen. The federal government heeded the request of the selectmen and appropriated $4,000 in 1810.

The lighthouse would serve a dual purpose. Not only would it mark the entrance to the harbor, it would also serve as a coastal light to guide traffic past the perilous Cohasset Rocks offshore. After surveying both points, Cedar Point was chosen to receive the lighthouse.

When the federal government established lighthouses, most times they would find a willing party to sell land at a fair rate. However, when it came to establishing the Scituate Lighthouse, as no land could be procured, it was taken by eminent domain.

The landowner, Benjamin Barker, wasn't happy with this outcome and made things difficult by denying access through his adjoining parcel of land. Barker frequently feuded with Simeon Bates, the station's first keeper.

Three locals from nearby Hingham were hired to construct the 25-foot-tall lighthouse. Nathaniel Gill, Charles Gill, and Joseph Hammond Jr. finished the station the week of September 19, 1811, a full two months ahead of schedule. Along with the tower, a one-and-a-half-story keeper's dwelling, oil vault, and well were constructed at a total cost of $3,200.

Soon after the lighthouse was erected, there was some controversy. The Boston Marine Society had some concerns with a fixed white light being displayed only 12-miles south of the Boston Light, also a fixed white light. Thinking that it might confuse mariners, they asked the local lighthouse superintendent, Henry Dearborn, to hold off placing the lighthouse into service until March 1812 so that discussions could be had regarding the characteristic of the light.

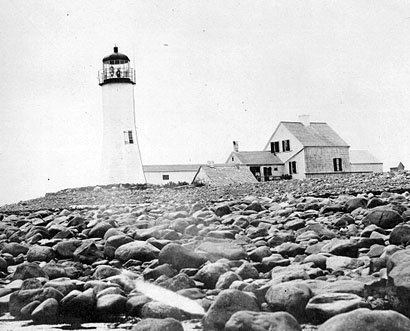

Scituate Lighthouse (Courtesy Coast Guard)

Scituate Lighthouse (Courtesy Coast Guard)

The Boston Marine Society had recommended an eclipser be installed which would give the Scituate Lighthouse a "flash" thus making it easy for a mariner to distinguish this lighthouse from the Boston Lighthouse. The other recommendation the society made was to obscure some of the range of the light which would result in an annual savings of $174.

Although the recommendations were made, none of them were adopted. Instead, the lighthouse went into service displaying a fixed white light on April 1, 1812. Ironically, the same issue arose a few years after the Highland (Cape Cod) Lighthouse was established in 1797. Again, the recommendation was to install an eclipser to make the lighthouse flash.

The apparatus was never installed in the Highland Lighthouse either. Instead, the Boston Lighthouse was given a flashing characteristic to help distinguish it from the surrounding lights in late 1811 with the adaptation of new equipment installed by Winslow Lewis.

Simeon Bates, the station's first keeper was appointed in December 1811. Together with his wife Rachel, the couple had nine children and he would remain on the job until his death in 1834 at the age of 99.

The War of 1812 would see many British frigates attack the harbors that dot the New England coast line. On June 11, 1814, British forces made their way into Scituate Harbor and plundered and burned many of the vessels anchored there. In response, Keeper Bates fired two rounds from a small cannon as the ship left.

Several months later, another man-of-war, the La Hogue had entered the harbor; however Keeper Bates and most of the family were away from the station. Left in charge were his daughters, 21-year-old Rebecca and 17-year-old Abigail. Although there were muskets at the lighthouse, Rebecca knew that if they fired on the troops, the British would have attacked the village.

What would happen next would earn the girls the nickname the "American Army of Two." Rebecca, fond of military music, ordered her sister to take a drum while she took the fife. Staying out of site, the two girls began to play Yankee Doodle hoping to scare off the troops. Much to their surprise, the British fled the harbor thinking that the town's militia was approaching.

Although Rebecca Bates signed an affidavit attesting to the truth of the story, some don't believe the event took place citing historical records that show the La Hogue was elsewhere at the time of the alleged event. Many historians do believe it and think perhaps the Bates girls mistook the identity of the ship. To date, the fife played by Rebecca is still on display at the keeper's house.

Given the short stature of the tower, its height was increased in 1827. Contractor Marshall Lincoln was employed to add a 15-foot brick addition to the stone tower and install a new lantern. When complete, the lantern displayed a fixed white light from seven lamps, while lower windows, added during construction, displayed a red light from eight lamps. The red light was produced from red glass placed against the windows.

Lt. Edward W. Carpender of the U.S. Navy was tasked with reporting on many of the lighthouses, and in 1838 he assessed the Scituate station.

This is a double light in a single tower; the lower light red, the upper white. It is not apparent why this should be a double light, when a single one would answer all the purpose. There is no other red light in Boston bay, so that, by having this a single red light, it is not possible it should be mistaken. Accordingly, I recommend its conversion into a single red light.

Arranged as the lights now are, the lower one only twenty feet above the level of the sea, and made in the manner it now is, it is not possible they should be of much service. To know them, you must approach near to them; for, being only fifteen feet apart, they blend at a short distance, and appear like a single light. Every consideration urges the conversion of this light into a single one of a distinguishable color; for, as I have said, there being no other red light in the bay, it is not possible it should be taken for any other; and having fifteen feet more elevation, it will be visible so much the farther. Some work was done on the tower in 1841 when Winslow Lewis had installed a new lighting apparatus and lantern in the tower. Inside the new lantern was 11 lamps arranged in two tiers backed by 14-inch reflectors. The lower area, which displayed the red light, was outfitted with found lamps also backed by 14-inch reflectors.

The following year, in 1842, civil engineer I.W.P. Lewis, a nephew of Winslow Lewis, inspected the station. Always critical of his uncle's work, he called out many areas in his report such as the base resting on the beach without any foundation below the surface, woodwork within the tower being more or less rotten, broken plates of glass in the lantern, lamps "leaky and burnt out," and reflectors out of plumb.

For the keeper's house, he had the following words: "The house is much decayed, all the frame work being more or less rotten; plastering scaled off the rooms; underpinning settled; floors settled; leaky in the roof and about the windows; chimneys smoky. A new dwelling house is very much needed here."

The report goes on to talk about the proximity to the Boston Lighthouse and how this light is routinely mistaken for it. And much like Lt. Edward Carpender's report of 1838, he spoke of the uselessness of the red and white lights.

The light-house here has, from some unknown cause, been repeatedly mistaken for Boston light, and vessels have run in during easterly storms, passed the light, and found themselves hard and fast ashore, before discovering their mistake. Other vessels have been wrecked in Minot's ledge, four miles to the northward, by mistaking this for Boston light...The small amount of tonnage owned at Scituate may be, and is undoubtedly, benefited by the convenience it affords in showing the entrance of the harbor; but to the navigation Boston bay, this light is, and always has been, a positive injury, and the cause of several heart-rending shipwrecks. The distinction of a red and white light here is altogether useless, and a wasteful expense, for the reason that the red light is only visible upon a close approach that would lead to casualties...This light should be reduced to a simple beacon of one lamp, instead of fifteen now used. It would then fall into its proper mark, and not be likely to cause such accidents as heretofore.

The keeper at the time of the inspection was Ebenezer Osborne. His statement in the report echoed many of the same items pointed out by I.W.P. Lewis. Slight improvements were made as a result of the report, but a new lighthouse would not be forthcoming at this location, instead it was planned for off-shore, at Minot's Ledge on the Cohasset Rocks.

Construction of what would become the Minot's Ledge Lighthouse would start in the spring of 1847. Although the apparatus and workmen were swept from the rocks several times during the summer that year, there were no casualties. By January 1, 1850, the 75-foot open-work iron lighthouse was complete and lighted.

With the Minot's Ledge Lighthouse sitting off-shore marking the Cohasset Rocks and ledge, the Scituate Lighthouse was changed to a fixed red light and would only serve to mark the harbor. However, on April 16, 1851, the iron framework of the Minot's Ledge Lighthouse would fail during a gale plunging the lighthouse into a furious sea. Keepers Joseph Antoine and Joseph Wilson would perish during the incident.

The result of the failed Minot's Ledge Lighthouse brought renewed importance to the Scituate Lighthouse. Its light characteristic was changed from red to a fixed white light in October 1854 and a year later was upgraded to the recently adopted Fresnel lens.

To mark the area after the demise of the Minot's Ledge Lighthouse, a lightship was stationed off-shore from 1851-1860. The government would again attempt a lighthouse at Minot's Ledge. This time, to ensure it would withstand the punishment of the North Atlantic, it was constructed of two-ton granite blocks.

Construction of the new Minot's Ledge Lighthouse started on June 20, 1855 and would take five years to complete. The night of November 14, 1860, the Scituate Lighthouse was lit for the last time as the following night, November 15; the light at Minot's Ledge would be exhibited for the first time.

Although the lighthouse was officially decommissioned on November 15, 1860, an article in an 1890 newspaper stated that a light was hung in the lighthouse for many years "for the guidance of Scituate herring fishermen."

Between 1885 and 1890, to improve the harbor at Scituate, the federal government constructed a 630-foot breakwater. Years later, second breakwater was constructed. To help mariners enter the harbor, a lamp on a spar was placed at the end of the jetty on June 10, 1891.

The jetty lamp was carried away during a gale in early 1904. To remedy the situation, a new skeletal tower was erected. The new light, fueled by kerosene, displayed a fixed red light 31 feet above the ocean's surface. The keepers assigned to watch over the breakwater light lived in the Scituate Lighthouse dwelling, however; by 1924 a new automatic acetylene light reduced the need for keepers.

Although the keeper's dwelling at Scituate was used frequently, the lighthouse had been abandoned since 1860. At some point, the lantern was removed, and the tower capped off. In an attempt to save the lighthouse, the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution started a petition drive, gaining 600 signatures, which they presented to their congressional representative in 1907.

Little had happened over the years. Finally in 1912, Selectman Jamie Turner learned that the property was to be auctioned the next day. To stop the proceedings, carrying a check signed by the town's treasurer, his wife traveled by train to Boston that day.

Local residents appealed to their senator, Henry Cabot Lodge, to delay the sale. With the sale put on hold, residents amassed $4,000 to purchase the aging property. One of the contributors was William Bates, a grandnephew of Rebecca and Abigail Bates, the "American Army of Two."

It would take many years, but finally on June 28, 1916, the legislation needed to sell the lighthouse was passed. The act allowed the town of Scituate to purchase the lighthouse and maintain it as a historic landmark. By the following year, the sale was official.

As part of the maintenance, the town had a replica lantern built and installed in 1930. The station was minimally maintained over the years, but by the mid-1960s, the lighthouse needed considerable work. At the request of the Scituate Historical Society, the town appropriated $6,500 to have the work done.

To maintain the property and discourage vandals, resident keepers were hired to live in the house. The rent they paid goes directly towards the upkeep of the property. The resident keepers also serve as tour guides during the open houses hosted several times each year.

Although none of the resident keepers have seen ghosts, some claim that the lighthouse is haunted by Rebecca and Abigail Bates. Caretakers would sometimes hear the fife and drum over the noise from the wind and waves, and one resident swore she hear the fife and drum coming from the fireplace chimney.

The lighthouse was relighted in July 1991, however; it was visible to the land only. Several years later, after the installation of a plastic 250-mm optic, the lighthouse was relighted as a private aid to navigation. It displayed a flashing white light and was visible for nearly four miles out to sea.

By early 2004, many of the bricks were deteriorating. It appeared that the severe winters had taken its toll on the nearly 193-year-old tower. After consulting with masonry experts, the diagnosis was that the outer layer of bricks needed replacing. The funding for the work came from the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority, and by the following summer, the work on the tower was complete. A fresh coat of paint was applied leaving the tower looking like new.

Reference:

- America's Atlantic Coast Lighthouses (6th edition), Jeremy D'Entremont, 2005.

- Annual Report of the Light House Board, U.S. Lighthouse Service, Various years.

- The Lighthouse Handbook: New England: The Original Field Guide, Jeremy D'Entremont, 2008.

- The Lighthouses of Massachusetts, Jeremy D'Entremont, 2007.

- The Lighthouses of New England - 1716-1973, Edward Rowe Snow, 1973.

Directions: From MA-3A, follow First Parish Road east. It will change names to Beaver Dam Road, continue following this east. Turn left onto Jericho Road, and follow this northeast. It will change names to Lighthouse Road. Follow Lighthouse Road to the end.

Access: The station is owned by the town of Scituate and managed by the Scituate Historical Society. Grounds open. Tower closed.

View more Scituate Lighthouse picturesTower Height: 50.00'

Focal Plane: 70'

Active Aid to Navigation: Yes

*Latitude: 42.20500 N

*Longitude: -70.71600 W

See this lighthouse on Google Maps.