Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse

South Portland, Maine - 1897 (1897**)

History of the Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse

Posted/Updated by Bryan Penberthy on 2017-01-21.

Entering Portland Harbor from the south, mariners face a dangerous ledge, which runs from Fort Preble out into the main shipping channel. To make a safer approach, the United States erected the Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse in 1897.

Before the Lighthouse Board built the Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse, mariners would steer for the Portland Observatory, built in 1807, on Munjoy Hill. When it looked like Waterville Street ran right up to it, they knew they were in the correct channel.

While this technique worked well for smaller vessels that were easier to manage, larger and less agile vessels frequently ran aground on Spring Point Ledge.

One such disaster was the Nancy, a lime coaster out of Rockland, Maine, which ran aground on September 7, 1832. As the water reached the stored lime, it began to smolder, which soon set the schooner ablaze. As the fire was nearly impossible to extinguish, the population of Portland watched as the ship burned to the waterline.

Locals in Portland were incensed and petitioned Washington to do something, which responded with apathy.

A year before the wreck of the Nancy, Portland was hit with a fierce Nor'easter. As the storm also coincided with high tide, damage was excessive. To protect Portland Harbor, Congress authorized construction of a breakwater, which started in 1833.

Although the idea of the breakwater was sound, without a light at the end, it became a navigational nightmare for mariners as vessels had to squeeze through a narrow passage between the breakwater and Hog Island Ledge. To remedy this issue, the Lighthouse Board established the Portland Breakwater Lighthouse in 1855.

While the breakwater lighthouse, commonly called the "Bug Light," did effectively mark the passage into the harbor, it frequently became a scapegoat for marking the Spring Point Ledge. Even though it was only a mile away, it was ineffective at marking Spring Point Ledge.

Shortly thereafter, the Lighthouse Board had a spar buoy placed at the edge of where the main channel and the Spring Point Ledge met. However, the buoy did little to help during inclement weather and over the years, many vessels ran aground, such as the Mazaltan, the Seguin, and the Smith Tuttle. Nowhere was this truer than with the wreck of the Harriet S. Jackson on March 12, 1876.

The Harriet S. Jackson was heading from New York to Wiscasset, Maine to pick up a load of cargo bound for Cuba. As the weather grew worse, its crew spotted the Twin Lights at Cape Elizabeth and made for the safety of Portland Harbor.

As they were approaching the harbor, the captain ordered the crew to keep watch for the Portland Head Lighthouse, which was nearly impossible in the suffocating, gale-driven snow. They expected to see it a quarter-mile off the port side, but when they located it, it was directly in front of the vessel. Luckily, they were able to steer clear.

As they continued on, the captain ordered his crew to watch for the Portland Breakwater Lighthouse. For a brief second, the captain spotted a glimmer of light. After mentally calculating the ship's speed and distance, he was convinced it was the Bug Light and ordered "starboard helm."

What the captain did not know was the light that he spotted was a lamp in the window of a home near Fort Preble, not the Portland Breakwater Lighthouse. With that, the ship gently, but firmly, ran aground on the unmarked Spring Point Ledge. As the storm raged on all night, the seas continually picked up and dropped the Harriet S. Jackson on the submerged ledge.

As night gave way to morning, the crew realized they were only 12 feet from the Fort Preble sea wall. They were so close that the crew laid a plank from the ship's deck to the wall to send a crew member into town to tell of the wreck. With assistance, the crew was able to free the Harriet S. Jackson the following day.

After repairs, the vessel would return to sea. Nearly two decades later, the Harriet S. Jackson struck the shoals near Pollock Rip. Two hours later, the vessel finally floated free. It was soon determined that it was taking on water, so the captain, with intentions of anchoring close to shore made for landfall. As the weather was thick, it ran aground near the Monomoy Point Lighthouse before her crew could make out land. On September 20, 1898, Harriet S. Jackson sank, becoming a total loss.

To get a lighthouse erected at Spring Point Ledge, it would take seven steamship companies banding together to show that they moved an astonishing 518,362 people into Portland Harbor during the year 1890. The following year, the Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board recommended a lighthouse for Spring Point Ledge:

In view of the excellence and importance of the harbor, the very large number of vessels which annually resort to it for refuge, the great number of passengers carried into it, which will doubtless steadily increase with the increasing number of people who resort to the coast of Maine in midsummer, and the frequency and density of the fogs at the very period when the passenger traffic is greatest, it is recommended that provision be made for the establishment upon Spring Point Ledge of a fog bell and a light of the fifth order.

The Lighthouse Board recommended Congress appropriate $45,000 for the tower, but it would be several years before the appropriation of $20,000 finally came through on March 2, 1895. A second appropriation of $25,000 was made on June 11, 1896, allowing construction to begin.

The Lighthouse Board made a contract with Thomas Dwyer and construction started in August 1896.A storm the following month did considerable damage to the iron plates that had been placed, and there were delays in obtaining new plates from Pennsylvania. Worked progressed slowly through the winter and by spring 1897, the light was complete.

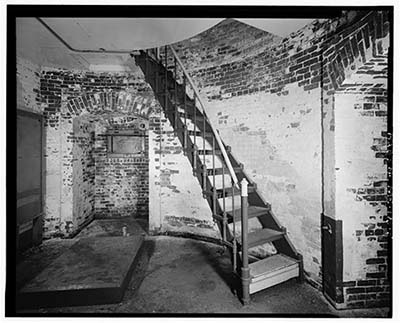

Basement of Light (Courtesy Library of Congress)

Basement of Light (Courtesy Library of Congress)

When completed, the cast-iron caisson was 25 feet in diameter, 40 feet tall, and was composed of 48 sections. One end was bolted to the ledge in fourteen feet of water, and then filled with concrete to a level of roughly 31 feet. Formed within the upper concrete section, were a cistern and a 239-gallon oil tank. The lowest level of the tower was the cellar, which made up the last nine feet of the cast-iron caisson.

What made this "sparkplug-style" tower different from others was that the entire structure was not made of cast-iron, similar to the Hog Island Shoal Lighthouse in Rhode Island. Instead, the superstructure of the tower is made of brick, built upon the concrete-lined, cast-iron caisson.

The lowest level of the brick superstructure was the kitchen. The next section of the tower was the head keeper's quarters, followed by the assistant keeper's quarters. At the top of the tower was the watch room and the lantern, both of which were made of cast-iron.

William A. Lane served as the station's first keeper, while Harry Philips served as the first assistant. The pair placed the tower and fog bell into service on the night of May 24, 1897. When completed, the caisson was painted black and the tower red. However, by November, to increase its visibility, the tower was painted white.

From the lantern, a fifth-order Fresnel lens exhibited a red flash, every five seconds. One sector exhibited a white light to indicate to the mariner that they were in a safe channel to proceed into Portland Harbor. Alongside the tower hung a fog bell that sounded a double blow every 12 seconds, operated by a striking machine run by 800 pounds of weights.

As the station was a stag station, keepers found things to occupy their time. One keeper figured out that 56 times around the station deck was roughly equivalent to a mile, only to fall through an open hatch while jogging. Another keeper played cribbage and built model ships, and Aaron Augustus Wilson carved wooden ducks.

Aaron Augustus Wilson, commonly known as "Gus", served as the third assistant keeper at the Twin Lights at Cape Elizabeth before becoming an assistant keeper at Spring Point Ledge, a position he held from 1917 to 1931. Prior to joining the Lighthouse Service at age 50, he made a living as a fisherman and boat builder.

Gus Wilson passed the time carving wooden duck decoys. It was said that he "whittled every spare moment," and created more than 5,000 carvings during his life. Unlike decoys carved by his contemporaries, Wilson's carvings were known for highly varied head and wing positions.

His carvings included variety of bird species, including ducks, shorebirds, seagulls, and songbirds, as well as African animals and some smaller species of marsh birds. Most of his carvings were sold to the Walker & Evans sporting goods store in Portland for 75 cents each, but others he simply gave away.

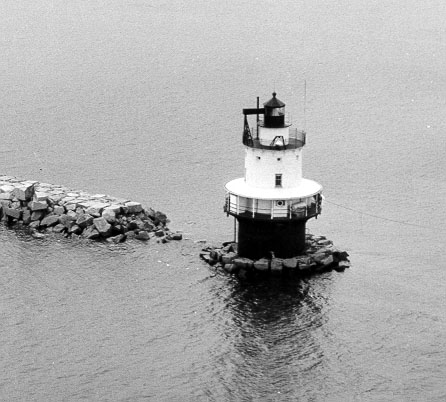

Breakwater under construction (Courtesy Coast Guard)

Breakwater under construction (Courtesy Coast Guard)

Starting in the 1940s, many of Wilson's creations became highly sought after, which sent their prices soaring. Several of his pieces have gone for more than six figures at auction, with the highest fetching $195,000 at an auction in July 2005. His works have been displayed at the Boston Museum of Fine Art and the Shelbourne Museum in Vermont.

Prior to the erection of the breakwater, the cast-iron caisson was frequently damaged by ice. To remedy the issue, large granite blocks were placed around the base in the 1930s. Construction of the 900-foot breakwater, which today links the lighthouse to shore, didn't start until June 6, 1950 and was completed by June the following year.

Both the Spring Point Ledge and the nearby Portland Breakwater Lighthouse were electrified in 1934. At that time, a second submarine cable was ran to the Portland Breakwater Lighthouse, allowing the keepers at Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse to monitor and operate the light remotely.

The Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse was automated in May 1960, and at that time, the Fresnel lens was removed. A new 300mm lens, lit by a 36-watt incandescent lamp took its place.

The Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 21, 1988. Today, it is also listed on the State of Maine Register of Historic Structures and has been listed by the National Trust for Historic Preservation under the "Save America's Treasures" program.

The Maine Lights Program, started in 1993 by Peter Ralston of the Rockland-based Island Institute, allowed for the transfer of lighthouses to local agencies with a personal interest in the structure's survival, while allowing the Coast Guard to maintain the light within the structure.

Under the Maine Lights Program, the City of South Portland and the Southern Maine Technical College applied to co-own the Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse, but the threat of potential litigation caused the city to withdraw its application. A handicapped-rights activist threatened to sue if the breakwater wasn't made handicapped-accessible.

The Portland Harbor Museum formed the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust in early 1998 to acquire ownership of the Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse. The group got around the litigation issue by pointing out that the breakwater was owned by the Army Corps of Engineers, and therefore the owner of the lighthouse is not responsible for access.

In Rockland, Maine, the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust formally accepted the ceremonial deed to the lighthouse on June 20, 1998.

One of the first projects undertaken by the group was replacement of badly deteriorated iron canopy over the structure's lower gallery. The project was carried out by Atlantic Mechanical Inc. of Wiscasset, Maine, and was completed in July 2004.

Other work carried out by the trust includes having cracks in the caisson sealed and the lighthouse exterior repainted in 2012, and portions of the interior painted in 2013.

While researching the whereabouts of fifth-order Fresnel lens that came out of the Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse, volunteers found a list of classic Fresnel lenses compiled by the American Lighthouse Coordinating Committee.

While looking through the list, the volunteer found the serial number, H.L. 331, which was the serial number of the lens of the Spring Point Ledge Light. Additional research turned up that it was in a private collection of Steve Gronow, owner of the Maritime Exchange Museum in Howell, Michigan.

The Maritime Exchange Museum is also currently in possession of the Fresnel lens from Michigan's Belle Isle Lighthouse. At one time, both lenses were listed as for sale on the Maritime Exchange Museum's website, but neither sold.

Mr. Gronow explains how the Spring Point Ledge lens came into his possession:

"We obtained it from the widow of the owner of Automatic Signal, which is the company that removed the Lens in the 1950s and converted it to a modernized optic. The Lens was given to him by the Coast Guard official in charge of that area back in those days. Both of them are now long gone, and his widow said that they had the lens for over 50 years before her husband passed away. It was his personal legacy to his career in Navigational Aids and the family treasured it very much."

The United States of America, acting on behalf of the United States Coast Guard filed a lawsuit on September 6, 2016 stating that the both lenses belong to them and are seeking to retrieve both lenses.

According to the lawsuit, per Work Order 60-3275 to automate the Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse stated that:

"[a]ll aids to navigation equipment and material that has been discontinued by action of this work order . . . shall be returned to C[oast]G[uard] Base, S. Portland."

The lens was purchased from Henry-Lapaute of Paris, France in in 1896 for $3,200, and is estimated to be worth roughly $250,000 today. The litigation is currently ongoing.

The Spring Point Ledge Light Trust opens the lighthouse to visitors most weekends from June through Labor Day, as well as special group tours by request. The group is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that relies on donations, ticket sales, and grants to support the lighthouse. All donations are tax-deductible to the extent permitted by law. Donations can be made at their website, www.springpointlight.org.

Reference:

- Annual Report of the Light House Board, U.S. Lighthouse Service, Various years.

- The Lighthouses of Maine: Southern Maine and Casco Bay, Jeremy D'Entremont, 2013.

- Lighthouses of Maine, Bill Caldwell, 1986.

- "Lens Rediscovered," Keith Thompson, Lighthouse Digest, July 2009.

- "New Canopy for Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse," Jeremy D'Entremont, Lighthouse Digest, August / September 2004.

- "False Light Led to Shipwreck at Spring Point Ledge," Staff, Lighthouse Digest, May / June 2015.

- "The U.S. Government Is Suing for a Set of Lighthouse Lenses," Danny Lewis, Smithsonian.com, September 16, 2016.

- "South Portland's Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse needs significant repairs," Alex Acquisto, Bangor Daily News, February 16, 2015.

Directions: From downtown Portland, follow Highway 77 across the Casco Bay bridge. Continue on Broadway until reaching the stop sign at the entrance to Spring Point Marina. Turn right on Benjamin W Pickett Street. Continue to the end and turn left on Fort Road. Proceed through the campus of Southern Maine Community College until reaching the parking area on the waterfront. The lighthouse will be to your right.

Access: The lighthouse is owned by the Spring Point Ledge Light Trust. Grounds open. Tower open in season.

View more Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse picturesTower Height: 40.00'

Focal Plane: 54'

Active Aid to Navigation: Yes

*Latitude: 43.65209 N

*Longitude: -70.22389 W

See this lighthouse on Google Maps.