Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse

Portsmouth, New Hampshire - 1878 (1771**)

History of the Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse

Posted/Updated by Bryan Penberthy on 2016-08-24.

Due to the natural harbor at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, settlement started in the early 1600s. By the mid-1600s, thanks to dense forests surrounding the Piscataqua River basin, Portsmouth Harbor had a well-established shipbuilding industry.

As Portsmouth Harbor was one of the oldest and busiest ports of colonial America, requests for a lighthouse date back as early as 1721. In 1765, a group of petitioners once again called for a lighthouse. In their petition, they noted that funds had been set aside more than 20 years earlier via the Loan Act and noted that "if Such a building was then Estimated of such Importance, to the safety of Navigation & benefit of Trade it is much more So now by the Increase of both."

Although the petitioners were authorized to evaluate Odiorne Point as a location for a lighthouse and to come up with a plan and cost estimates for construction, the project once again stalled.

It wasn't until April 4, 1771 when Royal Governor John Wentworth noted that the amount previously set aside was insufficient to establish a lighthouse. As an alternative, Wentworth proposed a "proper Lanthorn" be raised on the flagstaff on the grounds of Fort William and Mary.

The proposed lantern on the flagstaff was soon abandoned in favor of a proper lighthouse. Contractor Daniel Brewster was paid a sum of 372 pounds, 11 shillings, and one penny to erect a 50-foot tall wooden tower, clad with shingles. An iron lantern with a copper roof topped off the tower. The light was emitted from three oil lamps.

The tower was constructed on the grounds of Fort William and Mary, making it the first lighthouse established at a military installation of the British Colonies in the United States. The light was first placed into service on June 8, 1771.

The commander of Fort William and Mary, Captain John Cochran, was also placed in charge of the lighthouse. He most likely delegated daily lighthouse duties to the soldiers.

In 1772 Captain Cochran wrote to the royal governor stating that the funds provided were not enough to maintain the light. He requested an additional 20 pounds so that the "Light might not fail."

In July 1773, Captain Cochran again wrote a letter to the royal governor pleading for additional funds, saying that he was "in a Considerable Advance for the Light, and its [sic] not in my power to Continue and Keep up the light any longer." He requested an additional 20 pounds or else he would have to let the lighthouse go dark.

By 1774, just before the start of the American Revolution, the light was darkened. During the revolution, the tower served as a lookout post to watch for ships and was eventually renovated and relighted in 1784.

After the American Revolution, the commander of the fort delegated lighthouse duties to a soldier named Elias Tarlton. As no residence was supplied for him inside the fort, he would walk from his home a few hundred yards away.

In 1789, a new federal agency named the United States Lighthouse Establishment was set up. The new agency was operated under the Department of the Treasury and Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, was placed in charge. Shortly after that, many individual states began to cede their lighthouses to the newly commissioned Lighthouse Establishment.

When Governor Langdon wrote to Congress stating that he would be ceding control of the Portsmouth Harbor lighthouse, he also recommended that the new federal government should take control of the land where Fort William and Mary stood. He closed the letter recommending that a "Battery might be placed there to protect our harbor." The transfer took place in February 1791.

Due to the tower's importance, in 1793, President George Washington ordered that the light be maintained at all times and that the keeper live on site. As there was still no proper house, the keeper would be forced to live in a small building on the site.

Due to the stipulations, Keeper Tarlton refused the position and David Duncan took over as keeper in June 1793. By 1805, Duncan would get into frequent clashes with the soldiers at the fort, claiming that they had stolen his property. A fence between the keeper's house and the fort solved the issue in 1807.

By 1793, local merchants were petitioning to have the lighthouse repositioned to a more advantageous spot, which was closer to the shipping channel. Two locations were proposed. The first was Pollock Rock, which was outside of the fort walls and would be subject to gunfire. The other was much closer to the position of the 1771 tower's site, but would still be closer to the shipping channel.

1804 Portsmouth Lighthouse (Courtesy USCG)

1804 Portsmouth Lighthouse (Courtesy USCG)

Although Tench Coxe, Commissioner of Revenue had proposed several other locations, including Whaleback Ledge, Wood Island, and Gerrish Island, in the end, the location on Pollock Rock, about 100 yards east of the 1771 tower, was selected.

Although a stone lighthouse was recommended as it would be more durable and impervious to fire, when the bill was passed in March 1802, the specifications called for an octagonal wooden tower of yellow pine and a new keeper's dwelling.

The keeper's dwelling was erected first. Benjamin Clark Gilman of Exeter, New Hampshire was the contractor chosen for the project. Construction of the new tower started in the fall of 1803 and was finished in 1804.

The 80-foot tall wooden tower sat atop a stone masonry base. The diameter at the bottom of the tower was 40 feet and tapered to 12 feet at the top. The lighthouse had a focal plane of 82 feet, making the light visible for more than 13 miles.

As the light sat in the shipping channel on Pollock Rock, a footbridge was needed for access. As the original 1771 lighthouse was still standing in late 1805, plans called to have it dismantled and to use the wood to build the bridge. Unfortunately the wood was found not conducive for construction and it was sold after the old tower was dismantled in 1807. New wood was used to erect the footbridge.

After being taken over by the United States Government, Fort William and Mary was enlarged between 1807 and 1808 and renamed Fort Constitution. The following year, the keeper's house was moved away from the Fort Walls due to the vibration from the guns.

Most early lighthouses (late 1700s through early 1800s) commonly used spider lamps, which was a pan, filled with oil, and had multiple wicks. Winslow Lewis, a sea captain and inventor had developed a new lamp, which was a similar design to the Argand lamp.

After impressing the Lighthouse Establishment with the trials of his lamp's performance and low oil consumption, which were held at the Boston Lighthouse, he was awarded a contract in 1812 to outfit all lighthouses with his lamps. Later that year, the Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse was outfitted with eleven of his lamps backed with parabolic reflectors.

During the War of 1812, the tower was extinguished as to not aid the British. After the war, extensive renovations to the lighthouse, dwelling, oil vault, and footbridge were carried out.

New wood was installed on the exterior of the tower and then covered over with pine shingles. After that, three coats of white lead paint were applied. Atop the tower, a new wooden deck, sheathed with copper, was installed beneath the lantern.

Repairs were also carried out on the keeper's dwelling, which included new boards placed on the roof, new shingles on the exterior, and repairs for the windows and doors.

In 1820, a local named Allan Porter was appointed keeper to take over for David Duncan. By then, Duncan, who had been keeper since 1793 was of advanced age and in ill health. Porter would maintain keeper position until 1839, when he was forced out due to his political affiliation.

Civil engineer I.W.P. Lewis, the nephew of Winslow Lewis, visited the Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse in 1843 to produce a report on the state of the nation's lighthouses. In his report, he used the phrases "excellent piece of carpentry" and said it would "bear favorable comparison with its more modern neighbors."

He also noted in his report that with the establishment of the Whaleback Ledge Lighthouse in 1830, the Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse would become a simple harbor beacon and recommended its number of lamps could be reduced from 13 to 1.

As the importance of the tower was diminished, its height was reduced in 1851. The tower was reduced by 25 feet, leaving it 55 feet tall.

With the establishment of the Lighthouse Board in 1852, there was widespread adoption of the superior Fresnel lens. For the next several years, many of the nation's lighthouse were upgraded. The Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse received a fourth-order Fresnel lens in 1854.

1878 Portsmouth Light (Courtesy USCG)

1878 Portsmouth Light (Courtesy USCG)

In 1861, Elias Tarlton, the great grandson of the soldier with the same name that served as the keeper in 1784, was appointed the keeper of the Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse. He would serve as keeper until September 20, 1866 when he died of heart disease.

The original keeper's dwelling was in poor condition by 1870. That same year, the Lighthouse Board had recommended an appropriation of $2,000 for its replacement. Construction of the dwelling started in 1871, and by 1872, it was reported that the old one was taken down and the new one was erected on the same foundation.

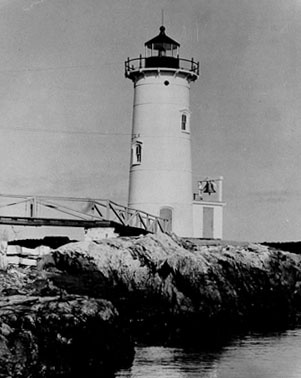

In 1878, the Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board had reported that the 1804 wooden tower was replaced with a new cast-iron tower:

54. Portsmouth Harbor, entrance to Portsmouth Harbor, New Hampshire - The old and decayed wooden light-tower was removed, and a new cast-iron tower set in its place.

The new 48-foot cast-iron tower was designed by Army Corps Office James Chatham Duane, the Lighthouse Board Engineer for Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts.

The new tower was erected on the same foundation that the 1804 tower stood on. The tower is made up of segments, each containing 12 cast-iron plates. The segments were formed in a foundry located in Portland, Maine and once on site, fastened together with nuts and bolts.

For added durability and insulation, the tower was then lined with a one-foot layer of brick. The air space left between the brick and the cast-iron plates provides the insulation.

Atop the tower was a 10-sided, cast-iron lantern. Inside the lantern was the fourth-order Fresnel lens, which was moved over from the old tower. The new tower displayed a fixed white light from a kerosene-burning lamp. It is reported that it was the first lighthouse in the United States to have a kerosene lamp as part of its original equipment.

When the lighthouse was moved closer to the Pollock Channel in 1804, access to the tower was via a footbridge. The bridge required frequent repairs and / or rebuilding over the years.

From the Annual Reports, the bridge length varies by year. In 1832, it was listed as 300 feet. In 1847, it was listed as 325 feet. When it was rebuilt in 1863, no length was given. However, in 1879, it was listed as 160, but a decade later, it was listed as 320 feet. The reason for the discrepancies is unclear.

A 12-foot by 18-foot fuel house was added to the station in 1892 and a brick oil house was built in 1903.

A 1,048-pound fog bell was added to the station in 1896. The bell was mounted to a small square building, which adjoined the base of the tower. The striking machinery was placed in a small shed attached to the base of the lighthouse. During periods of foggy weather, the bell would be struck with a single blow every ten seconds.

The following year, a survey was taken of the station, and the dwelling was moved 550 feet to the east. This was to make room for Battery Farnsworth. The dwelling would once again be moved in 1905, this time to make room for Battery Hackleman. This move required a new footbridge to be constructed.

After two close calls with military vessels running aground near the lighthouse in 1925, Navy officials complained about the quality of the light. In November of that year the light was converted to electric operation, replacing the finicky incandescent oil vapor lamp. Full electricity came to the station in 1934.

Over the years, many keepers had served at the Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse. The longest serving keeper was Joshua Card, having served 35 years. Card had originally served at the Boon Island Lighthouse off the coast of Maine, but took a pay cut to transfer to the Portsmouth Harbor light in 1874 and retired in 1909.

The last civilian keeper was Elson Small. Elson had started sailing at the age of 14, and made a career working for the U.S. Lighthouse Service. He had served at numerous lights along the coast of Maine, including the Lubec Channel Light, Avery Rock, and the remote Seguin Island Lighthouse at the mouth of the Kennebec River.

For Elson and his wife Connie, serving at the Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse was their first light station that was on the mainland. It was also the first time the couple had electricity. The Smalls called Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse home from 1946 to 1948, when Elson retired.

The Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse was automated in 1960. That same year, the Coast Guard established a base at Fort Constitution and housed personnel in the former keeper's house.

In 1998, the Coast Guard had the lighthouse restored. Seacoast Diversified Inc., was contracted to remove the lead paint from both the interior and the exterior of the tower, as well as to replace the rotting wood ceiling in the watch room. The cost was $73,000.

The American Lighthouse Foundation (ALF) took over care of the Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse in early 2000. The following year, the Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse was founded as a chapter of the ALF.

Over the years, the chapter has carried out many improvements, including reconstruction of the wooden walkway leading to the tower and restoration of the 1903 oil house.

In 2010, the organization's name was changed to the Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses to show that it had taken over care of the Whaleback Ledge Lighthouse in Kittery, Maine, which sits just offshore from the Portsmouth Harbor Light.

Although the lighthouse is only open during open houses on Sunday afternoons and during other special events, the grounds of Fort Constitution are open daily and provide excellent views of the lighthouse. It is worth a visit.

Reference:

- Annual Report of the Light House Board, U.S. Lighthouse Service, Various years.

- "Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse, New Hampshire - Part 1 of 2," Jeremy D'Entremont, The Keeper's Log, Spring 2015.

- "Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse, New Hampshire - Part 2 of 2," Jeremy D'Entremont, The Keeper's Log, Summer 2015.

- http://www.portsmouthharborlighthouse.org/ website.

Directions:From Portsmouth, take New Castle Ave. (Route 1B) east out of town. Turn left on Wentworth Road, and then make a quick right onto Sullivan Lane, which will lead to Fort Constitution. From here, you can park in the lot and walk to Fort Constitution. Great views of the lighthouse are available from the fort.

Access:The lighthouse is owned by the U.S. Coast Guard, but leased to the Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, a chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation. Grounds and tower open during tours.

View more Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse picturesTower Height: 48.00'

Focal Plane: 52'

Active Aid to Navigation: Yes

*Latitude: 43.07100 N

*Longitude: -70.70900 W

See this lighthouse on Google Maps.