Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse

Pompano Beach, Florida - 1907 (1907**)

History of the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse

Posted/Updated by Bryan Penberthy on 2016-03-07.

By 1900, most of the coastline of Florida had been marked by lighthouses. One exception was a dark stretch along the Atlantic Ocean between the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse and the Fowey Rocks Lighthouse, off the coast of Key Biscayne. To light that dark section of the Florida coastline, the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse was built in 1907.

During the 1800s, the United States worked to develop the Intracoastal Waterway, an inland waterway that ran along the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico in the United States. The Intracoastal Waterway utilized many natural features such as natural inlets, rivers, bays, and sounds. The benefit to the Intracoastal Waterway was that it allowed coastal trade while keeping vessels out of the open Atlantic Ocean.

One such natural inlet that was used was the Hillsboro Inlet, near Pompano Beach. The town of Hillsboro, Florida takes its name from Wills Hill to whom large land grants were made when the Florida Territory was under British control. Hill, better known in North America as the Earl of Hillsborough, served as Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1768 - 1772.

Near the end of the 19th century, several factors led to increased settling in the area. The first was the extension of the Intracoastal Waterway, which reached Biscayne Bay in 1890, and the second was the Great Freeze of 1894-1895, which destroyed many crops in northern Florida.

With the increase in settlers, more vessels began plying the waters offshore. The first request for a lighthouse at Hillsboro Inlet appeared in the Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board in 1884. The following year, it was repeated:

Hillsboro Inlet, Florida - The following recommendation, made in the Board's estimates last year for a new iron light-house at this place, is repeated:

This is an important point not yet lighted and is necessary to complete the system for this dangerous coast.

The request was repeated every year until 1887, when additional detail was added to the request. The new entry is listed below:

Hillsboro Inlet, off Hillsboro Point, between Jupiter Inlet and Fowey Rocks lights, east coast of Florida - The establishment of a light at or near Hillsboro Point, Florida would be of great assistance to all vessels navigating these waters. Steamers bound southward, after making Jupiter Inlet light, hug the reef very closely to avoid the current. The dangerous reef making out from Hillsboro Inlet compels them to give it a wide berth and to go out into the Gulf Stream. Vessels coming across from the Bahama Banks would be able to verify their position if a light were placed here, a difficult matter in case they fail to make Jupiter Inlet. The establishment of this light would complete the system of lights on the Florida Reefs.

The Board, therefore, renews the recommendation made in its annual reports for the last two years, that $90,000 be appropriated for this purpose.

Still, the requests were ignored. Finally, on February 12, 1901, a first-order lighthouse was approved provided that the cost did not exceed $90,000, however no appropriation was made. A little over a year later, $45,000 was appropriated on June 28, 1902.

As only half of the needed funds were available, little progress was made. By 1903, another $25,000 was appropriated. The Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board for that year detailed some issues that they ran into:

1007. Hillsboro Inlet, off Hillsboro Point, between Jupiter Inlet and Fowey Rocks lights, Atlantic coast of Florida - By the act approved February 12, 1901, the establishment of a first-order light at or near Hillsboro Point, Florida, was authorized at a cost not exceeding $90,000, and by act approved June 28, 1902, $45,000 was appropriated therefor, and a contract to build this station was authorize [sic] at a cost not to exceed $90,000.

The act approved March 3, 1903, made an appropriation of $25,000 for the light, making $70,000 available for use in its construction. A preliminary examination was made of the conditions in the vicinity of the inlet and a site south of it was provisionally selected. Preliminary survey was made, and borings were taken, and as the underlying material at this site was not satisfactory, it was decided that a further and more complete survey with borings should be made at available sites on the north side of the inlet. The Board recommends that a further appropriation of $20,000 be made, in order that the work of building this station may be carried to completion.

A site on the north side of the inlet was selected, and as no satisfactory arrangement could be made with the owners, the government started condemnation proceedings. Apparently the threat of the proceedings was enough to come to an "agreement." On November 9, 1903, the Department of Commerce and Labor purchased three acres of swamp land from El Field and Mary Osborn for $320. The following year, the plot of land was surveyed and building locations were selected.

The final appropriation of $20,000 was made on March 3, 1905, making the full $90,000 available for the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse. Bids for the construction of the lighthouse were advertised, with plans to open them on August 1, 1905.

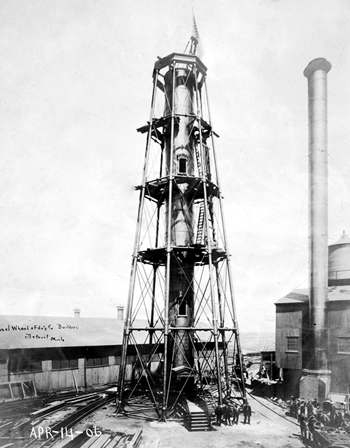

Hillsboro Lighthouse under construction (Nat. Arch.)

Hillsboro Lighthouse under construction (Nat. Arch.)

When the bids were opened that August, there were two bids for furnishing the metalwork of the tower. Of the two bids, Russel Wheel and Foundry Company of Detroit, Michigan was awarded the contract to furnish a 137-foot skeletal lighthouse.

Once the entire lighthouse was erected at the foundry, it was labeled and dismantled, to be shipped to Florida. It is reported that the lighthouse was shipped via Lake Erie, to Lake Huron, to Lake Michigan, and then via the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers to the Gulf of Mexico. From the Gulf of Mexico, it was floated around Key West and into the Atlantic Ocean, where after 4,000 nautical miles, it had arrived at Hillsboro Inlet.

The J.H. Gardner Construction Company of New Orleans, Louisiana was awarded the contract for clearing the land, laying the foundation, and reassembling the tower. The total cost for the work was $16,792.

G.W. Brown Construction Company of West Palm Beach, Florida was awarded the contract for the construction of five buildings. To house the keepers, three one-and-one-half story keeper's dwellings, painted white, were built about 100 feet northward of the tower. The other two buildings were a red brick oil house, built about 50 west of the tower, and a boathouse and boatways. The cost of the five buildings was $21,500.

Although the lighthouse was originally requested to be a first-order light, a contract in the amount of $7,250 was awarded in 1905 to Barbier, Benard & Turenne of Paris, France for a second-order bivalve Fresnel lens and rotating mechanism.

This is where many websites and books incorrectly report that the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse was built and displayed at the 1904 Great St. Louis Exposition. The tower itself wasn't built until 1906 and there is photographic proof in the National Archives showing the tower under construction with a date of April 14, 1906.

What was on display at the Great St. Louis Exposition of 1904 was the massive nine-foot, second-order bivalve Fresnel lens manufactured by Barbier, Benard & Turenne. Once the exposition was over, the government purchased this lens for installation at the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse.

Engineers chose to use an iron skeletal tower due to the threat of hurricanes as it would allow the wind and the waves to pass through the structure unabated. Although the tower was skeletal, it included an enclosed, circular staircase to shelter the keepers while climbing to the top.

The coloring of the tower was to not only make it unique, but to allow it to stand out when viewed from the ocean. The lower third of the tower was painted white to allow it to be seen against the trees, while the top two-thirds of the tower were painted black to allow it to stand out against the daylight sky.

Captain Alfred Alexander Berghell was appointed the head keeper of the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse with a salary of $800 per annum. At dusk, on the night of March 7, 1907, Captain Berghell lit the incandescent oil vapor lamp providing a beam of light seaward.

The following day, Henry A. Keys was assigned as the first assistant keeper and Robert H. Thompson was assigned as the second assistant keeper. Keys served until March 21, 1908, when he was replaced by Thomas E. Albury. Thompson served until June 1, 1908. He was replaced by Samuel R.A. Curry.

Twenty-five years before hurricanes were named, the "Great Miami" Hurricane would strike on September 18, 1926 as a category 4 hurricane with winds as high as 150 miles per hour. At the lighthouse, the storm surge washed away nearly 20 feet of sand, leaving eight feet of the concrete foundation exposed. The storm also caused damage to the dwellings, and carried away the boathouse and wharf.

To stabilize the point, an eighteen-foot wide granite breakwater was installed in 1930. The breakwater ran from the base of the lighthouse and extended 260 feet to the ocean.

In 1925, the lighthouse was upgraded from kerosene to DC electric power. Four 250-watt bulbs brought the light intensity to 1-million candlepower and was said to be visible for 18 nautical miles. The DC power was upgraded to AC in 1932. Although the candlepower stayed the same, it was achieved with only three 250-watt bulbs.

As oil hadn't been used in the lighthouse since 1925, the oil house was demolished in 1938. At this time, the staff was reduced by one, leaving only the head keeper and the first assistant to maintain the light.

The electric lights were again updated in 1966. The three 250-watt bulbs were replaced by one 1000-watt xenon bulb, which increased the light's intensity to 5.5-million candlepower, making it the third most powerful lighthouse in the world. The light was said to be visible for 28 nautical miles.

Automation, in the form of a photocell, was installed in 1974. This mechanism turned the light on at dusk and off in the morning. As the lens wasn't covered when not in use, it was left rotating non-stop to prevent damage to nearby properties from reflected sunrays.

That same year, each of the three keeper's cottages were renovated to be used as guest quarters for senior Coast Guard officers. Although the light was automated, one Coast Guardsman was assigned the title of "lighthouse keeper" and was to maintain the lighthouse and grounds. Four years later, the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1992, the mechanism that rotated the massive Fresnel lens failed. As a quick fix, the Coast Guard installed a 190-mm rotating lantern, which was mounted to the railing outside the lantern room. This much smaller, modern plastic optic reduced the beam to eight nautical miles.

Prior to learning that mercury was toxic to humans, it had many uses. One such use was in Fresnel lens, primarily the mechanisms that allowed the large, heavy lenses to rotate effortlessly. After sitting motionless for two years, it was determined that the mercury from the old rotation mechanism needed to be removed.

In 1995, the Coast Guard contracted with Chemical Waste Management Inc. of Pompano Beach, Florida to remove 400-pounds of mercury and clean the reservoirs, at a cost of $32,500. Worth Contracting of Jacksonville, Florida was then awarded a contract to clean mercury and lead-based paints from the lighthouse. This was carried out by sandblasting and repainting the tower with an epoxy-based paint. The cost for the cleanup was $98,000.

It was recommended the following year that the Coast Guard remove the second-order Fresnel lens, and replaced it with a more modern Vega 25 rotating beacon, which had a range of 10 nautical miles. Once locals discovered the plan to remove the historical lens, the Hillsboro Lighthouse Preservation Society was formed to stop it.

In 1997, Collins Engineering of Chicago, Illinois was awarded a contract to design a new ball bearing rotating mechanism to replace the decommissioned mercury float. Their contract also stipulated the removal and replacement of the existing electrical wiring and to renovate the service room to its original configuration.

On November 6, 1998, the Coast Guard Auxiliary volunteers installed the new ball bearing mechanism and restored the rest of the Barbier, Benard & Turenne Fresnel installation. On January 28, 1999, the second-order Fresnel lens was placed back into service. Its 5.5-million candlepower beam was once again visible for 28 miles into the Atlantic Ocean.

Exactly one month later, the newly-designed bearing unit failed, forcing the Coast Guard to reactivate the Vega 25 beacon. Over the course of the year, members of the Coast Guard Civil Engineering Unit designed a new bearing. In January of 2000, the design was sent to the Torrington Company of South Carolina to be built. On August 18, 2000, the new bearing was installed once again allowing the Fresnel lens to be used.

In June of 2003, the United States Postal Service chose the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse to represent Florida for a series of stamps featuring lighthouses of the Southeastern United States.

The Hillsboro Lighthouse Preservation Society opened the Hillsboro Lighthouse Museum and Information Center in March of 2012. Today, the lighthouse and grounds are open to visitors thanks to the work of the Hillsboro Lighthouse Preservation Society.

The Barefoot Mailman and the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse

During the early 1880s, the furthest south the U.S. Mail went was Lake Worth, Florida, just south of West Palm Beach. There was no mail service to the growing city of Miami. In 1885, the United States Postal Service set up a Star Route between Lake Worth and Miami, in which "beach walkers" contracted with the Post Office to carry the mail along a "barefoot route." The term "barefoot mailman" wasn't used until 1940.

The route, one way, was a total of 68 miles. Of the 68 miles, approximately 28 of those miles were via boat. The other 40 miles was covered by walking along the firm sand, closest to the water. The entire round-trip took six days.

Several people had filled the "barefoot mailman" role over the years, but the most widely known was James E. "Ed" Hamilton, who took over the position in 1887 when contractor E.R. Bradley quit. Hamilton had passed through Hypoluxo, Florida on October 10, 1887 and was making his way south. Although he was not feeling well, he continued on.

Hamilton should have returned to Lake Worth at the end of the week. When he didn't return, a search party was launched. Searchers found his clothes and mail sack on the north bank of Hillsboro Inlet, and the boat the Hamilton would have used to cross the inlet was missing. It was most likely that the boat was on the other side of the inlet, and when Hamilton arrived, he set his personal effects down and set out to retrieve the boat.

It was during that crossing that something most likely happened. He could have been attacked by a shark or an alligator, or drowned in the strong current while swimming the nearly 200-foot-wide inlet. It is unknown as his body was never recovered. James E. Hamilton was declared dead on October 11, 1887. Andrew Garnett took over the route after Hamilton's disappearance.

In 1973, artist Frank Varga created a ten-foot-tall stone statue to honor the legend of James "Ed" Hamilton and the barefoot mailmen. The statue stood outside the Barefoot Mailman Restaurant for years until the restaurant closed. At that time, the statue was moved in front of the Town Hall. In 2003, the statue was moved to the grounds of the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse.

Over the years the statue had suffered at the hands of Mother Nature and vandals. The statue had broken fingers, broken heel, chipping concrete, and peeling paint, but it was when vandals broke the statue's dagger that it was irreparably damaged.

To preserve the memory and commemorate the careers of the barefoot mailmen, the Hillsboro Lighthouse Preservation Society undertook a project in 2011 to have the statue recreated in bronze. The group sought grants and donations to help fund the effort. On March 19, 2012, the Hillsboro Lighthouse Preservation Society unveiled an 8-foot tall bronze statue perched atop a 5-foot tall granite pedestal. Today, the statue still points the way to the Hillsboro Inlet.

Reference:

- Florida Lighthouses, Kevin M. McCarthy, 1990.

- Annual Report of the Light House Board, U.S. Lighthouse Service, Various years.

- Guide to Florida Lighthouses, Elinor De Wire, 1987.

- "HLPS Starts Fund to Replace Barefoot Mailman Statue at Hillsboro Inlet Light Station," Staff, Big Diamond, April 2011.

- "Historical Events of Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse Station," Art Makenian (USCG Auxiliary), Big Diamond, February 2007.

- Hillsboro Lighthouse Preservation Society website.

Directions: From I-95, exit at West Atlantic Blvd (State Route 814). Follow that right to the ocean and North Ocean Blvd (Route A1A). Then head north towards Hillsboro Beach. It is along this street that you will see the Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse. You can get some really good pictures from the little park on the right hand side of the road just before crossing the drawbridge.

Access: The lighthouse is owned by the Coast Guard and managed by the Hillsboro Lighthouse Preservation Society. The tower and grounds are open during tours.

View more Hillsboro Inlet Lighthouse picturesTower Height: 137.00'

Focal Plane: 135'

Active Aid to Navigation: Yes

*Latitude: 26.25900 N

*Longitude: -80.08100 W

See this lighthouse on Google Maps.