Clark's Point Lighthouse

New Bedford, Massachusetts - 1869 (1797**)

History of the Clark's Point Lighthouse

Posted/Updated by Bryan Penberthy on 2013-09-15.

Nestled along the banks of the Acushnet River at the confluence of Buzzards Bay sits the port town of New Bedford. It was first explored as early as 1602 by Bartholomew Gosnold, but wasn't settled by Europeans until some fifty years later. It would take until 1787 before it would be incorporated as the town of New Bedford.

The late 1700s would see a lot of growth and development in the town. The town's first post office and newspaper were started in 1792, and some four years later the first bridge was constructed in town. Although farming was the main way of life in the area, by the late 1700s, residents began engaging in whaling.

One such individual, William Rotch, Jr., is attributed with having brought the whaling industry from Nantucket to the Bedford Village, which is today known as New Bedford. He set up a whale fishery on the ten waterfront acres of land his grandfather had purchased in 1765. He eventually came to run the family business of harvesting the whales, processing the parts into saleable goods, and then bringing the goods to market.

1804 Clark's Point Lighthouse (Courtesy Coast Guard)

1804 Clark's Point Lighthouse (Courtesy Coast Guard)

As early as 1797, a wooden lighthouse was erected on Clark's Point by local merchants. The structure lasted about a year before being lost to a fire. It was reported that thunderstorms were in the area at the time, so it is possible that a lightning strike started the fire, although it is unclear.

A new lighthouse, financed and rebuilt by local mariners and merchants was constructed one year later, and was lighted on the night of October 12, 1799. A bill passed in the spring of 1800 shifted the burden of upkeep from the merchants and mariners to the United States. This tower again would only last a few years before succumbing to fire on August 5, 1803.

It would take nearly a year before Congress would appropriate $2,500 for the reconstruction of the lighthouse. An Act of Congress approved on March 16, 1804 stated:

Sec. 3. And be it further enacted, that it shall be lawful for the Secretary of the Treasury to cause to be rebuilt, in such manner as he may deem expedient, the lighthouse at Clark's point within the town of New Bedford, in the state of Massachusetts.

The new stone tower, constructed in 1804, was 38-feet tall. Upon completion, the workers were rewarded with a 100-gallon pot of chowder. The first keeper of the lighthouse built his own house on site as none was provided by the government. By 1818, the tower would be heightened an additional four feet and topped with a new cast-iron lantern bringing the focal plane to 50 feet.

U.S. Navy Lieutenant Edward W. Carpender inspected the lighthouse in 1838 and had several recommendations, which included a reduction of the number of lights from ten to six. Part of the reported is listed below:

Doubtless four lamps, properly attended, would be abundant here; but I shall recommend six, suppressing the upper tier as being entirely superfluous, and not required by the nature of the navigation. I visited this light in the forenoon, and have good reason to think that fewer lamps, differently attended, would afford equal light; one of the lamps was without a fountain, and appeared not to have been used the previous night. Two of the chimneys, or tube-glasses, were broken. And some of the others so much smoked as to show that they had been carelessly trimmed. The reflectors were not bright, and did not appear to have been recently cleaned.

Lieutenant Carpender also commented on the effectiveness of the light, stating that it would have been better placed 150-yards southward, directly on the southwestern point of Egg Island shoal.

By the 1840s, New Bedford was experiencing as much success with whaling as Nantucket. Whale meat and oil was extremely valuable, and the industry provided many jobs to the locals. Two things would help propel New Bedford past Nantucket as the most powerful whaling town and become one of the richest per capita cities in the world.

A local blacksmith by the name of Lewis Temple set about a way to revolutionize the whaling industry and created the toggling harpoon. Simply known as the toggle iron, the device was a harpoon that would lodge under the blubber of the whale making it virtually impossible for the animal to break free.

The other factor that would drive New Bedford forward was the depth of the port. Nantucket Harbor was relatively shallow with many moving sand bars; this meant that many of the larger sailing vessels could not cross the bar. New Bedford didn't have this problem. Many of the newer and larger vessels which sat deeper in the water could still call New Bedford Harbor home.

Because of the importance of New Bedford Harbor as a whaling center, and attacks of the past such as the American Revolution and the War of 1812, discussions on the establishment of a permanent military installation started again in the late 1840s.

By 1851, a new set of lamps and reflectors were installed in the tower to augment the effectiveness of the light.

The permanent military installation would get its start on September 24, 1857 when the federal government purchased the farm of Edward Wing Howland on Clark's Point. Granite from nearby Fall River was brought in for the construction of a three-tiered fort. But before the fort could be completed, the Civil War broke out, which put construction on hold.

During the war, New Bedford Mayor Isaac C. Taber feared for the port. Confederate ships were already prowling Long Island Sound and Buzzards Bay capturing and destroying New Bedford's whaling fleet. In order to protect the harbor, Mayor Taber and the City Council formulated a plan for self-defense.

The plan called for an earthen fort just west of the federal fort under construction. The earthen fort, completed on May 11, 1861, was named Fort Taber in honor of the mayor and was fortified with brass and iron cannons. Local citizens were recruited to occupy the fort to protect the approach to the harbor.

By the spring of 1863, the federal fort at Clark's Point's granite walls had overshadowed the earthen walls of Fort Taber. The cannons of Fort Taber were moved to the new granite fort, and Fort Taber was no more. Although the new fort was never officially given a name, many locals referred to it as Fort Tabor.

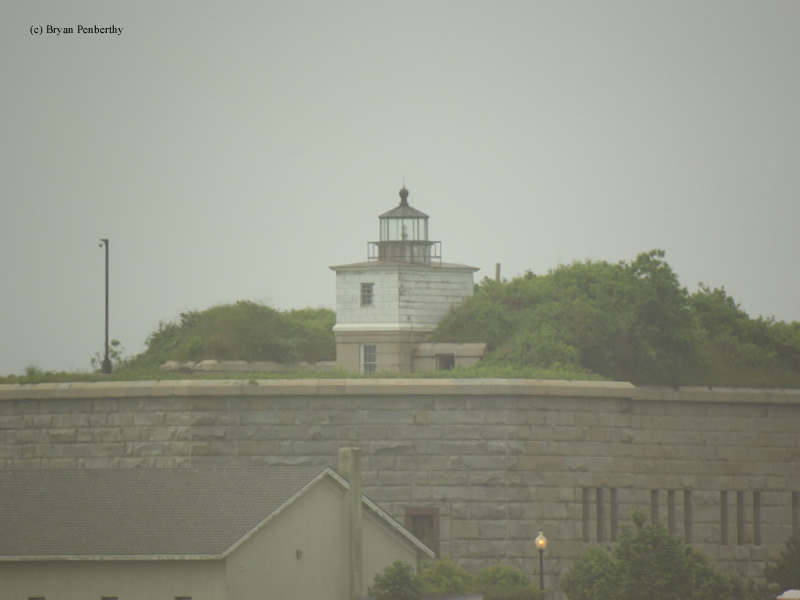

By 1869, the granite walls were at a height that blocked the view of the lighthouse. To rectify this, a rectangular wooden tower was implemented on the northern wall of the fort. The lantern from the stone tower was moved to the new lighthouse atop the fort's wall making it 68 feet above sea level. June 15, 1869 was the date the new tower went into service. The old stone tower remained until it was demolished in 1906.

After the conclusion of the Civil War, the War Department halted construction of the fort in 1871. This left the third tier incomplete. The unused granite blocks of the fort were redirected for construction of a seawall on the eastern side of the point.

Not only was New Bedford at the forefront of the whaling industry, many factories also called New Bedford Home. By the late 1800s, it had become the third largest city for manufacturing in Massachusetts. The port of New Bedford would see nearly 500,000 tons of goods pass through it in year 1890 alone.

With the amount of shipping traffic entering and leaving the port (more than 1800 vessels in 1890), it would become clear that a new lighthouse would be needed to replace the aging Clark's Point Lighthouse at Fort Tabor. Recommendations had started appearing in the Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board in 1889.

A new lighthouse called Butler Flats, was completed in 1898 rendering the Clark's Point Lighthouse obsolete. Amos C. Baker, Jr., keeper of the light at Clark's Point, accepted the appointment of keeper at Butler Flats, and subsequently moved over to the new tower. Also in 1898, the fort that the locals were calling Fort Tabor was officially named Fort Rodman.

After the culmination of World War II, Fort Rodman was declared surplus and was unarmored. By the 1970s, most of the Fort Rodman acreage was partially sold to the City of New Bedford to be used as a future park and for educational purposes. A group called the Friends of Fort Taber was formed shortly thereafter and volunteered their time to restore the fort.

However, from the 1980s to the year 2000, the fort and lighthouse would fall victim to vandalism and neglect. Starting in the late 1990s, the City of New Bedford unveiled a plan to create a public park around the fort. The Fort Taber Historical Association was formed to head the preservation efforts.

Along with the restoration of the fort came the restoration and relighting of the Clark's Point Lighthouse. Restoration of the lantern was carried out at the city's waste water treatment plant's welding facility and other crews rebuilt the wood-framed upper section of the tower. The tower was relighted on June 15, 2001, which was the 132nd anniversary of the lighthouse's first illumination.

Directions: The lighthouse sits on the wall of Fort Taber in New Bedford. Follow Rodney French Boulevard to the end into Fort Taber Park.

Access: The lighthouse sits on the wall of Fort Taber. The grounds around the fort is open. The fort is open during special events only.

View more Clark's Point Lighthouse picturesTower Height: 59.00'

Focal Plane: 68'

Active Aid to Navigation: Yes

*Latitude: 41.59300 N

*Longitude: -70.90100 W

See this lighthouse on Google Maps.